This article introduces how NebulaGraph uses Jepsen test framework to ensure system linearizability.

Why Jepsen?

Linearizability here specifically means consistency in the CAP theory. In NebulaGraph, we guarantee strong data consistency in our key-value store.

So under such a consistency policy, we need to make sure:

A read happens BEFORE a write operation ends must read the previous write

A read happens AFTER a write operation ends must read the current write

Strong data consistency relies on a solid chaos testing plan which can affect a distributed system in many unplanned ways, which in turn helps uncover corner cases that are hard to detect in development.

This is how Jepsen comes into play.

What is Jepsen?

Jepsen is an open source software library for system testing. It is an effort to improve the safety of distributed databases, queues, consensus systems, etc.

Jepsen's author Kyle Kingsbury writes the test framework with Clojure, a functional programming language. He has then performed linearizability tests on some well known distributed systems and databases.

Currently Jepsen is still active on GitHub and it has become the actual benchmark for distributed systems.

Jepsen Test Process

Below is a chart depicting the Jepsen test process:

By default there are six containers in the cluster, one of which is the control node and the other five are database nodes (the nodes are named n1 - n5 respectively). As soon as the test starts, the control node will create a group of worker threads, each contains its own client, to access the database nodes simultaneously via the SSH protocol. The generator tells the client what operations it should perform against the system while the nemesis tells the client what fault the client should inject to the system.

The beginning, ending, and results of each operation will be documented in Jepsen's history folder.

When the test ends, the checker will analyze the history accuracy to verify if the results are linearizable. For the checker, you can use either the built-in validation model provided by Jepsen knossos, or you can define custom model per your own business requirements.

Things to Consider Before the Test

To make sure the Jepsen test runs smoothly, please be sure to complete the following configuration before you start the test:

- Define operations in the DB API: download, install, start, and end

You may delete the database log files when the test ends. Or you can specify a location for the log files and Jepsen will copy them to its own log folder for later analysis.

- Choose a client

Be sure to have a client to access your database. The client can be either Clojure based such as etcd verschlimmbesserung, or JDBC and so forth. Then you need to define the client API to tell Jepsen what operations can be performed against your database.

- Select the test model in Checker

For example, Jepsen will generate a chart for latency and the entire test process for performance test (checker/perf) and an html page containing timestamps of all operations for timeline test (timeline/html).

- Define failure types

Specify the types of faults you want to inject to the system in the Nemesis component. Some common ones include partition-random-halves and kill-node.

- Configure worker thread parameters

Configure the operations within the worker thread in the generator process, as well as the time interval of each operation and each fault injection.

Running Jepsen Test on NebulaGraph

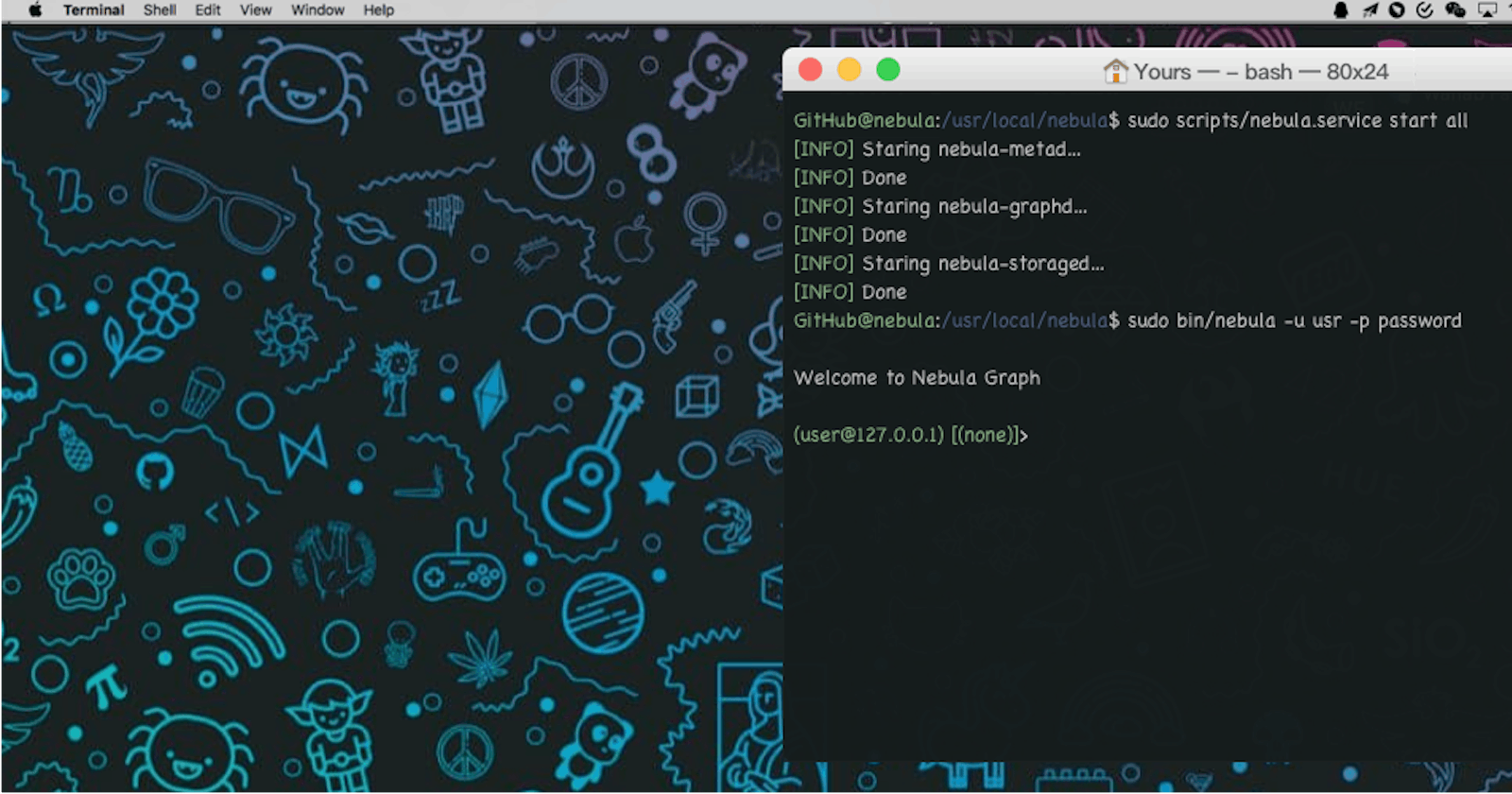

NebulaGraph has three components: meta layer, graph layer, and storage layer. The three layers work as a whole for NebulaGraph service to run normally.

The Jepsen test is mainly on the storage layer.

During the test against the KV storage API, we have built an eight-container cluster:

One Jepsen control node

One meta node

One graph node

Five storage nodes

The cluster is built in Docker and started by Docker-compose. Bear in mind the following two things:

There should be a subnet within the cluster so that the nodes can communicate with each other.

Install SSH service and enable passwordless login to the five storage nodes for the Jepsen control node.

We have generated a jar package with the Java client and added it to the Clojure dependencies. Then the client can perform operations (put, get, cas, etc.) against the database. In addition, auto retry logic has been added to the Java client so that proper retry mechanism is enabled to make sure the operations have been successfully completed. Nebula-Jepsen, the test program developed by NebulaGraph, has three test models and three common chaos injections.

Jepsen Test Models

single-register

A single-register stores only the value of one key. While the test program reads and writes the database simultaneously, each successful write changes the value stored in the register.

Then compare the read value from the database with the value in the register to see if they are consistent, which can validate whether the system is linearizable.

Since it's a one-key register, the key is the same during the test and the value of the key is randomly generated upon operations.

multi-register

A multi-register however stores values of multiple keys. The validation process is the same as single-register, only that the keys are also randomly generated in multi-register.

Below is a sample of read and write operations during the test:

4 :invoke :write [[:w 9 1]]

4 :ok :write [[:w 9 1]]

3 :invoke :read [[:r 5 nil]]

3 :ok :read [[:r 5 3]]

0 :invoke :read [[:r 7 nil]]

0 :ok :read [[:r 7 2]]

0 :invoke :write [[:w 7 1]]

0 :ok :write [[:w 7 1]]

1 :invoke :read [[:r 1 nil]]

1 :ok :read [[:r 1 4]]

0 :invoke :read [[:r 8 nil]]

0 :ok :read [[:r 8 3]]

:nemesis :info :start nil

:nemesis :info :start [:isolated {"n5" #{"n2" "n1" "n4" "n3"}, "n2" #{"n5"}, "n1" #{"n5"}, "n4" #{"n5"}, "n3" #{"n5"}}]

1 :invoke :write [[:w 4 2]]

1 :ok :write [[:w 4 2]]

2 :invoke :read [[:r 5 nil]]

3 :invoke :write [[:w 1 2]]

2 :ok :read [[:r 5 3]]

3 :ok :write [[:w 1 2]]

0 :invoke :read [[:r 4 nil]]

0 :ok :read [[:r 4 2]]

1 :invoke :write [[:w 6 4]]

1 :ok :write [[:w 6 4]]

In the sample above, the number on the left indicates the worker (i.e. thread No.) which performs the operation. Every time an operation is initiated, the record is tagged as invoke and the column right next to it specifies if it's a read or a write. The info within the square brackets are the details of the operation. Let's see some examples:

:invoke :read [[:r 1 nil]]This row records a read operation has been initiated intending to read the value of key 1. Since the operation has just started, the value of the key is unknown, hence "nil" next to 1.:ok :read [[:r 1 4]]This row records a successful read operation and the value of key 1 is 4.

You may also notice a nemesis operation in the sample above.

:nemesis :info :start nilThis row records the beginning of a nemesis operation. The next record indicates that nemesis intends to isolate n5 from the cluster so that it's unable to communicate with other nodes within the cluster.

cas-register

Besides the read and write, there's a cas-register to validate cas (compare-and-set) operations.

Below is a sample code from the test:

0 :invoke :read nil

0 :ok :read 0

1 :invoke :cas [0 2]

1 :ok :cas [0 2]

4 :invoke :read nil

4 :ok :read 2

0 :invoke :read nil

0 :ok :read 2

2 :invoke :write 0

2 :ok :write 0

3 :invoke :cas [2 2]

:nemesis :info :start nil

0 :invoke :read nil

0 :ok :read 0

1 :invoke :cas [1 3]

:nemesis :info :start {"n1" ""}

3 :fail :cas [2 2]

1 :fail :cas [1 3]

4 :invoke :read nil

4 :ok :read 0

Just like the single-register test, the key remains the same during the entire cas operation test process. Let's take a look at some examples:

:invoke :read nilThis row records the initiation of a read operation. Since it's just the beginning, the result is nil.:ok :read 0This row records a successful read operation. The value returned is 0.:invoke :cas [1 2]This row records the initiation of cas operation, i.e. update the value to 2 if the read result is 1.

Introducing Failures in Jepsen

Below are the three types of failures NebulaGraph has injected to the cluster for chaos testing purpose.

kill-node

The control node of Jepsen will randomly kill a certain database service on a node several times during the entire test. When a node is killed, the available nodes decreased by one in the cluster. After a certain time, the database service of the node is started and the node will rejoin the cluster.

partition-random-node

Jepsen will randomly isolate a node from others during the test, so that there is no communication between this node and other nodes. Then Jepsen will repair this network isolation after a certain time to restore the cluster to its original state.

partition-random-halves

In this common network partition, the Jepsen control node randomly cuts the five database nodes into two parts, one of which has two nodes and the other has three. Communication will be resumed after a certain period of time as shown below.

Test Results

Jepsen will analyze the test results according to the requirements and get the results of this test. From the following output of the console, we can see the test is passed.

2020-01-08 03:24:51,742{GMT} INFO [jepsen test runner] jepsen.core: {:timeline {:valid? true},

:linear

{:valid? true,

:configs

({:model {:value 0},

:last-op

{:process 0,

:type :ok,

:f :write,

:value 0,

:index 597,

:time 60143184600},

:pending []}),

:analyzer :linear,

:final-paths ()},

:valid? true}

Everything looks good! ヽ(‘ー`)ノ

Auto-Generated timeline.html File

After the test is completed, you will get an auto-generated timeline.html file. The follow picture shows part of this file.

The above picture shows the timeline of operations. Each execution block has the corresponding execution information.Jepsen verifies the linearizability based on this operation order. This also acts as Jepsen's core. We can also track faults with the HTML file.

Performance Analysis Generated With Jepsen

Following are some performance analysis charts generated with Jepsen. This project name is basic test, please note that your project name may be different.

We can see the read and write latency in this chart. The above grey area incites the timing of fault injection. In this test we injected random killing node.

This chart shows the success rate of read and write. We can see the highlighted bottom red area is where failures occurred. This is because the control node stopped the partition leader's nebula service when killing a node. The cluster needs to re-elect at this time. When new leader is selected, the read and write are restored to normal.

Conclusion

Jepsen has some short comings, such as the test can't run for a long time, because a large amount of data will cause out of memory during the verification phrase.

However, in actual scenarios, many bugs require long-term stress tests and fault simulations to discover, and the stability of the system also requires long-term running to be verified. Meanwhile, when testing NebulaGraph with Jepsen, we also found some bugs that we've never seen before, some of which may never happen in use.

Currently, we are using Jepsen to test NebulaGraph on daily basis. We release the newly-updated code to the Docker Hub every day to perform continuous tests of the latest images with the Nebula-Jepsen.